Paul Hindemith

© 1946, by Associated Music Publishers, Inc.

Printed in U.S.A.

This book seeks to provide exercises which--if applied in the right way--must infallibly supply such fundamental theoretical knowledge. [pvii]

A musician brought up on the method of Solfège, as practised in countries under the influence of French or Italian musical culture . . . the disadvantages of this method show up later in the musician's course of study: it is extremely difficult to introduce students so trained to a higher conception of harmony and melody, and to bring them to a certain independence in their own creative work. They either cannot take the step out of their narrow concept of tonality (which by the uniform nomenclature for a tone and all its derivations is distorted almost to the point where reason turns into nonsense!), or they plunge more easily than others into what is assumed to be a new freedom: tonal disorder and incoherence. [pviii]

After these observations the aim of this book ought to be clear: it is activity. Activity for the teacher as well as for the student. Our point of departure is this advice to the teacher: Never teach anything without demonstrating it by writing and singing, or playing: check each exercise by a counter-exercise that uses other means of expression. And for the student: Don't believe any statement unless you see it demonstrated and proved; and don't start writing or singing or playing any exercise before you understand perfectly its theeoretical purpose. [pxi]

© 1937 by Associated Music Publishers, Inc.

Translation Copyright, 1942, by Associated Music Publishers, Inc.,

Revised Edition Copyright, 1945, by

Associated Music Publishers, Inc.

Printed in the U.S.A.

page 183

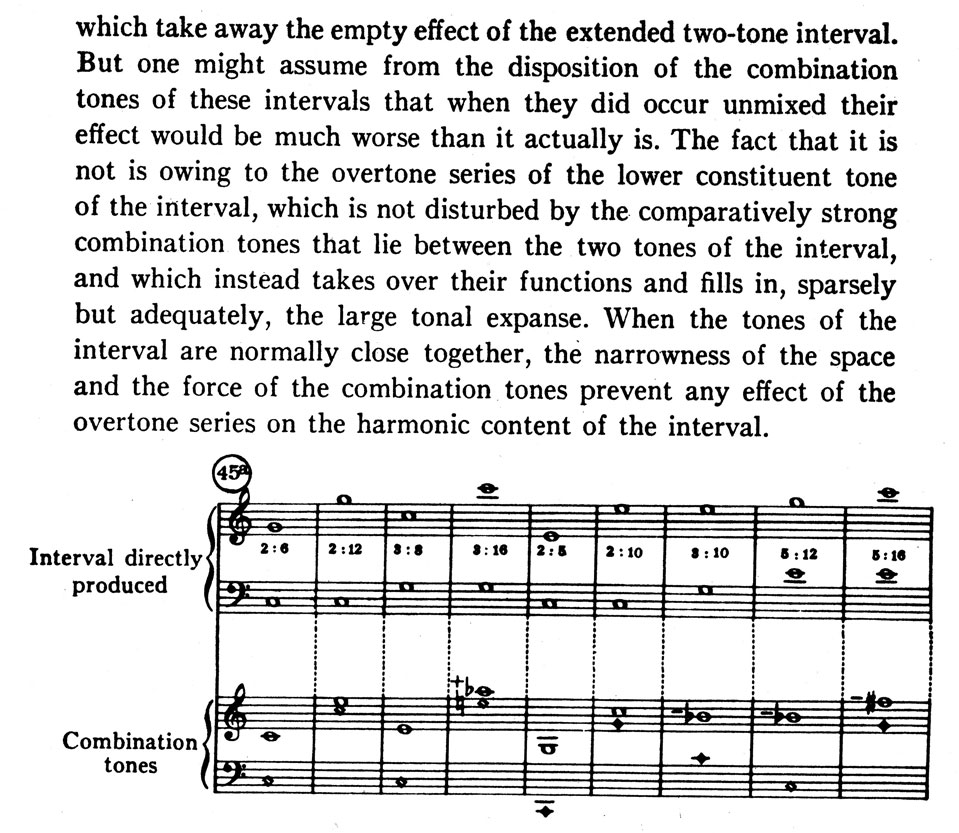

Once one has taken the step into the realm of equal temperament, one is tempted to increase the advantages it has over all other intervallic systems; unhindered access to every region of a tonality and absence of any commatic regulation. Could not the stimuili afforded by this carefree calculation be heightened if we replaced our twelve-tone division of the octave by a different number of tones? . . . .

. . . if we take a number exceeding twelve tones within the octave, we find it promising, the more so because we may get a chance to reduce the minor but ever-present toxic effect of impure intervals by diminishing the amounts of the tolerances. . . .

. . . our natural twelve-tone system, with its tendency towards maximum purity and its flexible commatic regulations achieved with the aid of expanded or contracted intervals readily tolerated, is doubtless the best one we can find. In its tempered form it is still close enough to nature so that its deviations are not felt as new intervals and so that it can be used together with the untempered form without causing serious disturbances.